REGENERATING

landscapes

We need to alter how we live to protect our future on earth

That may involve changing what we eat, how we travel, the way we create energy and the ways we work. It also means giving nature a huge helping hand to fight back.

Planting forests is one of the most effective ways of removing carbon from the atmosphere and avoiding the most disastrous effects of climate change.

Forests also provide homes, food and sanctuary for scores of wildlife, from birds in the canopy to insects on the forest floor.

The world has awoken to the necessity to plant more trees. In the UK, the government has committed to plant up to 30,000 hectares of trees per year, across the UK, by 2025.

Now we need to find lots of different places where these ambitions can take root. For a number of years now, Forestry England have been taking former industrial sites and transforming the disused land into areas where communities have space to play, seek adventure or find escape, and where wildlife can flourish. In this article, we explore some sites where landscape regeneration has been taking place, to see what the effects have been for wildlife, local communities and the environment.

The following photos show Sence Valley in Leicestershire where in just 25 years its coal mining history has been transformed.

4,000 years ago, Neolithic settlers began chopping down trees and setting up farms. Between the 17th and 19th centuries, the Agricultural Revolution brought an unprecedented increase in food production. During the second half of the twentieth century, vast numbers of people began migrating to and increasing the size of urban centres.

Our history books are full of landscape changes based on choices made by people. All our forests have been shaped by humans and many retain the clues of previous land uses.

Earthen ramparts of historic Castle Neroche, Somerset

Earthen ramparts of historic Castle Neroche, Somerset

One of the biggest influences on UK land use was the industrial revolution, which set the wheels in motion for a vast increase in the production of coal.

Coal mining peaked in 1913 and remained relatively stable until after the Second World War. From the 1950s, mines began to close down. By the end of the twentieth century, there was only a handful still open.

Today, demand for coal continues to fall with a focus instead on renewable and low carbon energy production.

So what happened to all the mines? In some places, they’ve been transformed into forests. The results speak for themselves.

A new beginning

Between 1982 and 1996, almost eight million tons of coal was extracted from an opencast mine to the north of Ibstock in Leicestershire. That’s the equivalent of 24 Empire State Buildings being taken out of the ground.

When the mine closed, the landscape was left desolate and dark.

Fast-forward a quarter of a century and the site is unrecognisable from its industrial past. Today, Sence Valley Forest Park is a vibrant green haven for people and wildlife.

“We are extremely proud of the transformation of Sence Valley over the last 25 years. Through careful management by our expert Foresters the site is unrecognisable from its recent past and has already started to provide timber through planned thinnings. In 2019, as the Forestry Commission celebrated its’ 100th anniversary, a new centenary woodland was created to expand Sense Valley further. 100,000 trees were planted throughout the year, giving wildlife even more of a foundation to bounce back.”

Andrew Stringer, Head of Environment and Forest Planning

More than 150 species of birds have been recorded in the area. Water fowl, swans and herons enjoy the lakes and waterways. Wildflowers including bee orchids flourish in the grassland meadows. Daubenton’s bats fly through the canopy above.

The forest is enjoyed by thousands of visitors each year. Trails lead walkers and cyclists through the trees. A bridleway offers horse riders stunning views across the vale.

Sence Valley is a striking example of a landscape finding new life. The project unmasks the power of trees and shows what can be achieved in a relatively short amount of time.

Beyond borders

The National Forest project that includes the transformation of Sence Valley bridges Leicestershire, Derbyshire and Staffordshire. The ancient forests of Charnwood and Needwood are also connected to the project.

Linking up green spaces is paramount to enable wildlife to move through the landscape. Forest Research provide a knowledge hub on their website about creating new woodlands as part of integrated landscapes and the impact they can have on biodiversity.

Without hedgerows, field margins and woodlands, species can become obstructed by infrastructure such as roads and building developments. Planting trees is one of the best ways of creating wildlife corridors to help woodland species move more freely.

The following maps show The National Forest before planting in 1991, and in 2016 as green corridors start to emerge.

Credit: The National Forest Company

“There are a number of grants available to landowners interested in planting trees on their land.

In doing so, we can bridge the gaps between different natural environments and give wildlife greater freedom to move across the country.”

Richard Greenhous, Director of Forest Services

Grants open to landowners looking to plant new forests come under three major funding schemes:

1. Woodland creation funding to improve biodiversity and water quality

2. Funding to plan and design a new woodland

3. Funding for new woodland to support carbon storage.

Different forests for different times

We know that planting trees is good for wildlife but it’s also important to plant the right trees in the right place.

When the Forestry Commission was established a hundred years ago, its primary focus was to replenish the country’s timber reserves. As a result, fast-growing conifers dominated the landscape.

Today’s climate and ecological emergencies present a very different reforesting challenge. Creating forests with urgency is still part of the agenda but diversifying planting is equally important. Andrew Stringer adds,

“For several decades we have recognised the value of planting a wider range of species, utilising the natural regeneration of our native species, and retaining greater age and genetic diversity in our forests.

Not only are diverse forests more resilient to climate change and disease, they create more vibrant and varied woodland ecosystems.”

Within a decade of being formed in 1919, the Forestry Commission had accumulated more than 100 forests spread over 600,000 acres of land. Over the past century, it has helped to more than double forest cover in the UK.

The scale and speed of reforestation during the 20th century is something that landowners can take inspiration from as we look to plant new woodlands that will endure for the next 100 years.

Working together

If we want to continue reviving our landscapes and help wildlife return, we all need to work together.

A group of partners in Manchester recognised the importance of a shared vision to breathe new life into their city.

The LIVIA (Lower Irwell Valley Integrated Action) site, which stretches from Clifton in Salford to Bury in Greater Manchester, brought charities, businesses and public sector bodies under one roof to rejuvenate an area that had been neglected for years.

After heavy industry closed down, the disused landscape was forgotten. Fly tipping, vandalism and motorbike scrambling made it dangerous and unwelcoming for local people. Wildlife was nowhere to be seen.

The Newlands project was launched in 2003 to regenerate derelict green spaces around Manchester and the North West. LIVIA was the flagship project and, at 199 hectares, presented a huge opportunity to unleash the potential of forests surrounding the city.

Over several years, LIVIA underwent a radical transformation to bring existing woodland into management, plant new woodland, create wetland and grassland habitats, and build waymarked trails for walkers, cyclists and horse riders. Over time, the area has become something the local community could be proud of. Today, the site is cared for by a thriving community of local volunteers, along with Forestry England’s expert team. They work hard to help keep invasive plants and anti-social behaviour at bay, while nurturing habitats for wildlife to flourish in.

As our cities continue to grow, in both population and size, it is essential we create spaces for nature as well. Trees and plants have a fundamental role to play in creating clean, green and healthy urban centres for people and wildlife.

A future to be proud of

How we act today will determine the world inherited by future generations.

Fortunately, forestry is an industry that looks long into the future. Every forest that is planted has its own plan that envisages how the land will be looked after for 30, 50 or even 100 years.

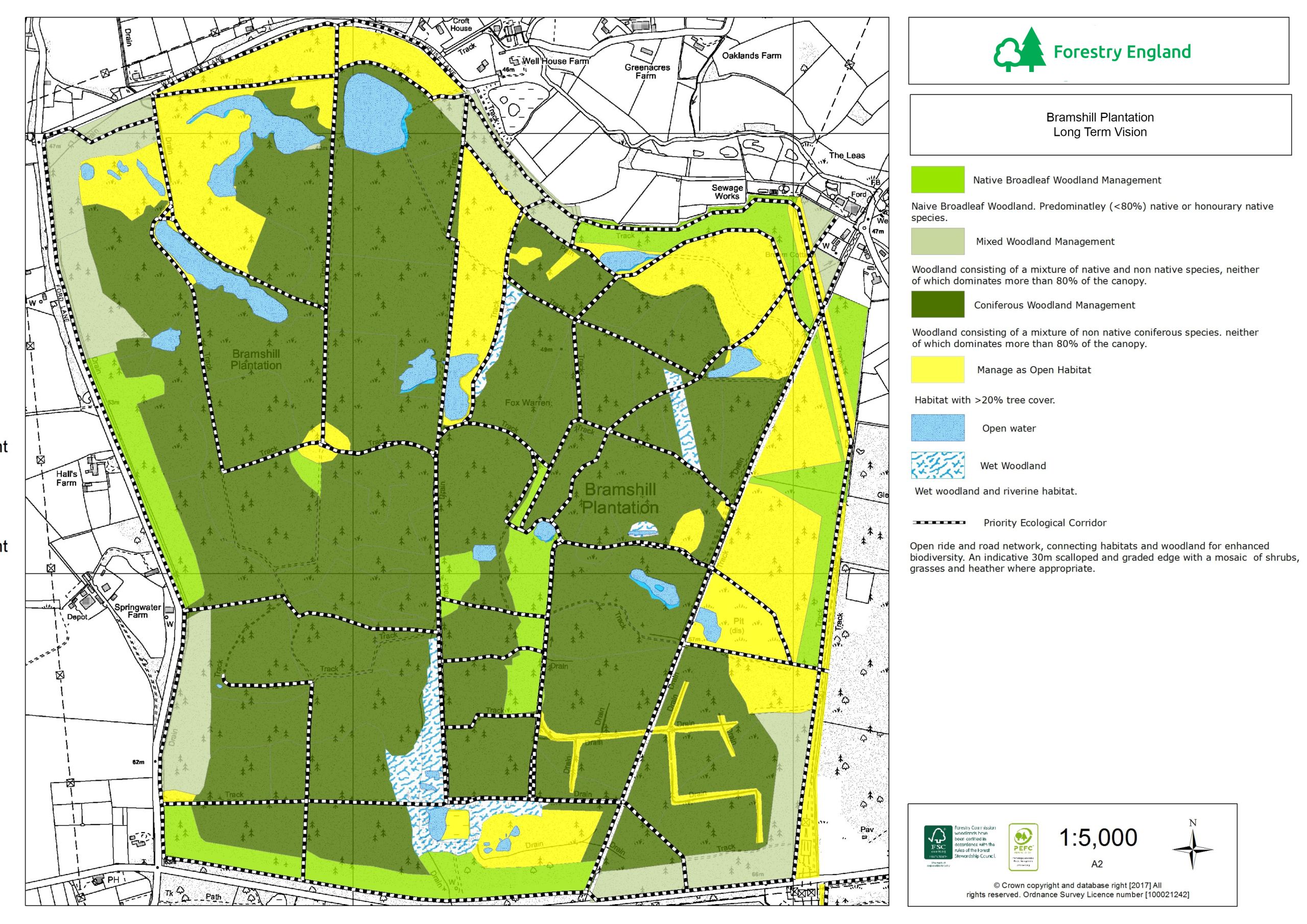

The award-winning strategy for Bramshill Forest in Hampshire sets out how the woodland will be resilient to climate change and support productive forestry, while protecting lowland heath, scrub, ponds and bare earth habitats.

A former quarry and landfill site, Bramshill is now almost unrecognisable from that time. Today, the open habitats and heathland support ground nesting birds including nightjar, woodlark and rarely-seen Dartford warbler.

Forest glades are alive with butterflies and moths. The ponds and mires are visited by a rich assemblage of dragonflies and damselflies.

The site is a shining example of how good forest management creates breeding habitats for a plethora of wildlife, including listed species that haven’t been seen in the area for decades.

Bramshill is popular among walkers, cyclists and horse riders, while producing sustainable timber as well.

“Nothing unlocks the power of nature like forestry. A disused landscape such as an old quarry or mine can appear barren and devoid of life. Once you start planting trees, the possibilities are endless.”

Bruce Rothnie, Forest Management Director at Forestry England

We are England's biggest land manager and custodian of the nation's forests. Find out more information about the nation's forests, cycling, family days out, live music, arts, education, volunteering and buying timber from us.

We are the government department in England responsible for protecting, expanding and promoting the sustainable management of woodlands. Find out more information on grants, felling licenses, forestry policy, tree planting and woodland management.

We are Great Britain’s leading organisation for forestry and tree research, internationally renowned for evidence and scientific services in sustainable forestry. Find out more information on forestry research, publications, resources and services to the industry.